| 06/01/2018 | |

| THE ECONOMIST |

FOR the first time in its brief history, Italy’s maverick Five Star Movement (M5S) is going into a general election campaign as the front-runner. On December 28th President Sergio Mattarella dissolved parliament, clearing the way for a vote on March 4th. The latest polls give the M5S, which advocates direct, internet-based democracy and a hotch-potch of left- and right-wing policies, a lead of more than three points over the centre-left Democratic Party (PD), the dominant partner in Paolo Gentiloni’s coalition government. The inexperienced M5S, founded less than nine years ago, could thus get first crack at forming a government—a prospect that troubles markets already worried by Italy’s huge public debt (132% of GDP at the end of 2016).

Like other populist groups in Europe, the M5S thrives on frustrated expectations. In Italy disillusion is most intense among the young and educated. Two-and-a half years after graduating, Valentina Fatichenti works six months in every 12 helping students at an American university campus in her native Florence. Otherwise, she scrapes a precarious living teaching English in primary schools, translating and, occasionally, waitressing.

She has decided to vote for the M5S. Its appeal? “New faces,” she says. The M5S chooses its candidates in online polls of its members. Its candidate for prime minister, Luigi Di Maio, is 31, just three years older than Ms Fatichenti (the better known Beppe Grillo, M5S’s founder, is ineligible to run for parliament due to a conviction for manslaughter, in a car accident).

Nando Pagnoncelli of Ipsos, a pollster, says 25- to 34-year-olds are the group most likely to support M5S: four points above the average. Young voters are also more likely than their elders to back other radical parties such as the Brothers of Italy (FdI), which has neo-fascist roots, and the Northern League, which wants less immigration and more autonomy for northern Italy.

Young Italians resent the older generations, but not their parents, says Alessandro Rosina, who co-ordinated a recent study for the Istituto Toniolo, a think-tank. They are hostile to mainstream parties, trade unions and an ill-defined “ruling class”, which they blame for the vast gap between their incomes, job prospects and pension pots and those of their elders. The Intergenerational Foundation’s most recent “intergenerational fairness index” ranks Italy second from bottom in Europe, ahead of only Greece.

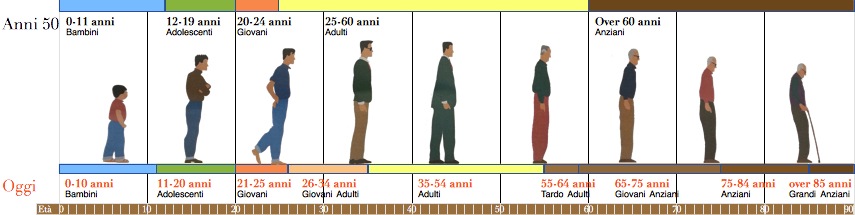

In 2014, the last year for which comparative data are available, what the government spent on Italy’s past (ie, on pensions) was more than four times what it spent on its future (ie, on education and training). But then, as Mr Pagnoncelli notes, it is the elderly who have the electoral clout. Voters over 55 make up 41% of the electorate, compared with 22% under 35—the effect of a steep decline in the birth rate dating back to the 1970s (see chart).

Many of the causes of Italy’s generation gap can be found in political choices made in the past 20 years that have favoured the old over the young. Italy’s low birth rate, coupled with disappointing economic growth, has prodded successive governments into pension reforms. But the way in which these have been carried out has placed on younger, generally lower-earning, workers the burden of providing not only for their own pensions, but also for those of the already retired. Labour reforms in 1997 and 2003 made it easier for bosses to hire new workers on short-term contracts, but did little to erode the job security of those already in permanent employment. And since the latter, along with pensioners, make up the bulk of trade-union membership, the unions have been keener to defend the privileges of those with jobs for life than to campaign for a more equitable distribution of benefits.