| 30/01/2023 | |

| NEY YORK TIMES - 30 Gennaio 2023 |

PIACENZA, Italy — On one side of a glass wall, three toddlers in a nursery school flattened play dough with plastic rolling pins. On the other, three old women in a nursing home tapped the pane to get their attention.

“Let’s say hi to the nonni,” the children’s teacher said before leading them through a door that connected the two rooms.

The children stopped to play with the magnifying glass of a delighted 89-year-old woman who had been using it to read obituaries. Then the toddlers, all 2 years old, took an elevator upstairs, where nursing home residents waited to read them picture books in a small library.

“It’s an extraordinary thing,” said one of the residents, Giacomo Scaramuzza, 100. “People think we are from two different worlds, but it’s not true. We are in the same world. And maybe I give them something, too. There is an exchange.”

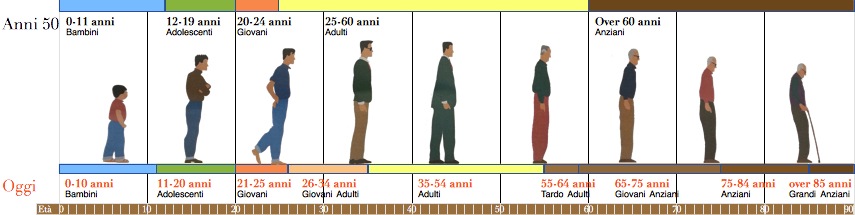

Italy’s population is aging and shrinking at the fastest rate in the West, forcing the country to adapt to a booming population of elderly that puts it at the forefront of a global demographic trend that experts call the “silver tsunami.” But it faces a demographic double whammy, with a drastically sinking birthrate that is among the lowest in Europe. Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has said Italy is “destined to disappear” unless it changes.

This month, Ms. Meloni’s government approved a new “Pact for the Third Age,” which she said would lay a foundation for health and social overhauls for Italy’s exploding population of old people. “They represent the heart of society, and a patrimony of values, traditions and precious wisdom,” said Ms. Meloni, adding that the law would prevent marginalization and the “parking” of elderly in institutions.

The overhaul essentially adopted, experts say nearly wholesale, a measure approved at the end of the previous administration of Prime Minister Mario Draghi. Critically, it followed Mr. Draghi’s lead in wrapping the legislation into the European Union recovery fund program, which ensures that it will be enacted.

“This is the acknowledgment that long-term care is a welfare policy,” said Cristiano Gori, who leads the Pact for a New Welfare on the Dependent, the umbrella organization that advocated the law.

A common hall at the nursing home. Italy’s population is aging at the fastest rate in the West.Credit…Elisabetta Zavoli for The New York Times

The new law, he said, will fix a system that is “a mess,” streamlining and simplifying government health care and social services, and getting local and national government into the growing field of long-term care. At the same time, it seeks to keep aging Italians in their own homes and out of institutions. A key innovation, he said, depends on funding by the Meloni government, but would give Italians a choice between unconditional cash benefits or larger in-kind contributions to be used for public care.

“The main shortcoming is that there is no money,” Mr. Gori said. The hope, he said, is that Ms. Meloni’s government, which sold itself to voters as being “family, family, family,” will make the program a real priority and fund it. But without more young people to join the work force and pay into pension and welfare systems, the whole system is imperiled.

Ms. Meloni, who once ran for mayor while pregnant, is Italy’s first female prime minister, and throughout her career, she has made raising the country’s perennially low birthrate and helping working mothers a priority.

But critics say her “Italians First” opposition to immigration — she has gone so far as to warn against “ethnic replacement” — hurts population growth. And Ms. Meloni’s government, slowed by local bureaucratic snags, has already delayed a program to build new nursery schools financed with 3 billion euros — or about $3.3 billion — in European Union recovery funds.

If Italy does not get serious about encouraging young families and working women to have children, “it will remain and forever be a country that gets older,” said Alessandro Rosina, a leading Italian demographer and an author of a “Demographic History of Italy.”

The reality of the gray new world poses a make-or-break test for Italy, making it a laboratory for many Western countries with aging populations, some experts said.

Some of Italy’s regions hope to delay that demographic time bomb by prolonging the period in which older people can work, be self-sufficient and contribute, and not be a financial drain on society. The center in Piacenza has sought to invigorate them with its precious resource of children. Before Covid sealed the nursing home off, children in the center ate and even cooked with the older residents. Now things are opening up again.